Auteur : Eliza Culea_

DOI : https://doi.org/10.48568/k3dv-xw20

[This multi-part article will briefly present some of the authors and positions adopted by scholars on the subject of cyberculture and bases itself on several introductory books that assemble in different ways key works and concepts of the past 20 years. It is meant to serve as a basic theoretical foundation for the exploration of contemporary works that try to tackle the problem of representation of cyberculture artifacts in the visual arts, with a specific interest in architecture and urban planning. It is also designed in complement with the existing contributions of Marion Roussel on the subject, intending to trace other readings of this vast domain. This first part focuses on how the word “cyberculture” has been coined and has aroused the interest of writers of the 80’s. Through its popular use, in science fiction in particular, we will question the fantasies of modernity this word reveals.]

Recorded by the Oxford English Dictionary as being first used in 1963 [1], ‘cyberculture’ became widely used in academic circles in the early 1990’s and it remains to this day a debated field of transdisciplinary studies, with various non-universally accepted definitions according to each authors’ own personal views and interests.

Cyberculture may be therefore only loosely defined as a way of thinking about the interaction between digital technologies and people, of how ‘we live together’. Its prefix cyber– refers to the cybernetics, the science of communication and control in living beings or machines, developed intensively since the Second World War and whose conceptual inception and popularization is attributed to Norman Wiener [2] in 1948.

The field (cybernetics ?) is predominantly interested in studying the implications that random events have, where a simple change could have far reaching implications and radical effects across entire closed system. Being profoundly transdisciplinary, cybernetics was initially focused on studies around electrical network theory, mechanical engineering, logic modeling, evolutionary biology and neuroscience. One of its fundamental research questions is that of the human interaction with complex and computerized machine systems, but it became officially separated from AI [3] studies in 1956 and continued focusing on applications in other fields, spanning research in domains as diverse as biology, psychology, computer sciences and art [4].

The suffix –culture, which is also elusive from a strict definition, has been described by Frow and Morris [5] as ‘a network of embedded practices and representations (texts, images, talk, codes of behavior, and the narrative structure organizing these) that shapes every aspect of social life’. The profoundly sociological connection that cyberculture as a term has, is evident already from its very first use: Alice Marry Hilton states in her fateful 1963 book that ‘In the era of cyberculture all the plows pull themselves and the fried chickens fly right onto our plates’ [6].

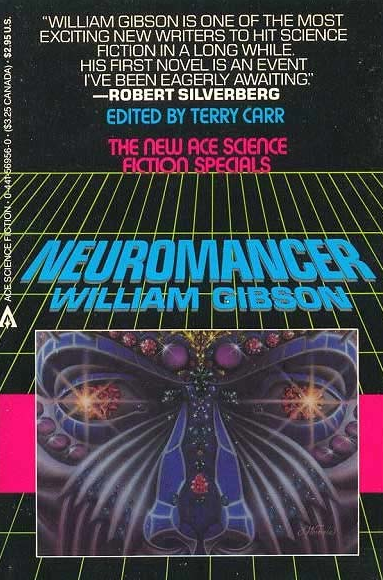

After two decades of limited appeal, the term ‘cyberculture’ receives a sudden and impressive boost in academic interest in 1984 after the publication of the Hugo and Nebula award winning novel titled Neuromancer by science fiction writer William Gibson. The intense enthusiasm was related mostly to a word found on the bottom right of the novels’ second page: cyberspace. The neologism was quickly defined by the author himself as

‘a consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts…A graphical representation of data abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the non-space of the mind, clusters, and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding…’ [7].

Later it was discovered that the author that fired up the imagination of an entire generation of programmers was still writing on the manual typewriter and not at all aware with the research conducted at ARPANET [8] which soon after gave the world the internet. Furthermore, it was not the plot of the book itself, however engaging and interested in impact of Artificial Intelligence on humanity, that received all the academic attention. It was his term of cyberspace together with the bleak and profusively electronic corporation driven world that was the backdrop of his novel.

It is interesting to take note on why did a science-fiction novel, mere literature, become the favorite bedtime story for grown men and women and heavily influenced the direction of their actual scientific research. Rob Kitchin in the introduction to the final chapter of The Atlas of Cyberspace [9] offers an explanation; he says that the alternative visions of ‘cyberspace’ provided by writers, film makers, artists and architects are important creative works that provide a critical sphere in which to question new concepts. Sometimes these artistic reflections become ‘blueprints’ or inspiration to the academic realm. This social constructivist claim, which is to be further approached in the second part of this article, underlines the mutual determinist relationship that seems to lie between technology and cultural artifacts, fitting right into cybercultures’ research realm.

Frequent science-fiction readers’ conception is that novels that adhere to this genre are not in fact related in any way to present time but actually pure speculations about the future. On this subject Gibson himself notes that for him science-fiction novels do not or better said should not attempt to claim to be clairvoyant, noting that the record of futurism in this genre ‘is actually quite shabby’[10]. He attributes only luck to the real crystallization of his cyberspace but notes that there remain major differences between the fictional version and reality, although admits liking when writers do get predictions right, such as Arthur C. Clarkes’ vision of the communication satellites. Gibson further states that his ‘novels set in imaginary futures are necessarily about the moment in which they are written’, but a reality ‘with the volume turned up, with all the knobs turned up’ [11].

To clarify this point, John Huntington writes in his essay ‘Newness, Neuromancer, and the End of Narrative’ [12] that science fiction is less about predicting a possible future rather than rendering visible somebody’s possibilities of hope. He also underlines that the novel, through its structure and subject alike, fitted perfectly with the label of postmodernism with which it would be even an understatement to call it as contemporary.

The impact that William Gibson’s work had on academia and in the dissemination of interest in cyberculture is also evident in his role for the 1990 MIT organized conference titled « Cyberspace: First Space ». In a brief and effective four page essay titled « Academy Leader », strategically placed by editor Michael Benedikt right after the introduction, Gibson states that he merely assembled the word cyberspace from ready and available components of language creating a ‘slick and hollow’ [13] concept which awaited to receive meaning. He was effectively underlining that the term was now out of his hands and unlike the equally popular term kipple [14] invented by Philip K. Dick that never crossed over into official use, cyberspace now had a life of its own shaped by its many current users. It is precisely these moments of crossing-over that reveal some aspects of the relationship between artistic production in the broad sense and technology and it is the purpose of the following parts of this article to retrace a general outlines of the research undertaken so far under the cyberculture umbrella.

Pour citer cet article

Eliza Culea, « Cyberculture Theory – Part 1: Origins and Science-Fiction », DNArchi, 14/11/2012, <http://dnarchi.fr/culture/cyberculture-theory-part-1-origins-and-science-fiction/>

[1] According to the OED, the term cyberculture first appeared in Alice Mary Hilton, Logic, computing, machines and automation, Spartan Books, 1963

[2] Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, Cambridge: MIT press, 1948

[3] Artificial Intelligence was founded as a distinctive discipline with the occasion of the Dartmouth Conference in 1956

[4] E.g. Telematic Art, Systems Art, Interactive Art

[5] John Frow, Margaret J. Morris, Cultural studies, in Norman K. Denzin, Yvonna S. Lincoln (eds) The Handbook of Qualitative Research, London: Sage, 2000, p.316

[6] Hilton, op.cit., p.16

[7] Gibson, Neuromancer, New York: Ace Books, 1984

[8] Advanced Research Projects Agency Network

[9] Martin Dodge and Rob Kitchin, Atlas of Cyberspace, London: Pearson Education, 2001

[10] William Gibson Interview, Paris Review, no.127, Summer 2011

[11] Scott Rosenberg, « The Man Who named Cyberspace: An Interview with William Gibson », 04/08/1994, retrieved on 6th of November, 2012 [en ligne], Digital Culture, URL: http://www.wordyard.com/dmz/digicult/gibson-8-4-94.html.

[12] John Huntington, « Newness, Neuromancer and the End of Narrative« , in Fictional Space. Essays on Contemporary Science Fiction, Shippey, T.(ed), Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1990

[13] Gibson, W., « Academy Leader« , in Cyberspace: First Steps, Benedikt, M.(ed), Cambridge: MIT press, 1990, p.27

[14] ‘Kipple is useless objects, like junk mail or match folders after you use the last match or gum wrappers or yesterday’s homeopape. When nobody’s around, kipple reproduces itself. For instance, if you to go bed leaving any kipple around your apartment, when you wake up there is twice as much of it. It always gets more and more.’. First appeared in Philip K. Dick, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, New York, Doubleday, 1968